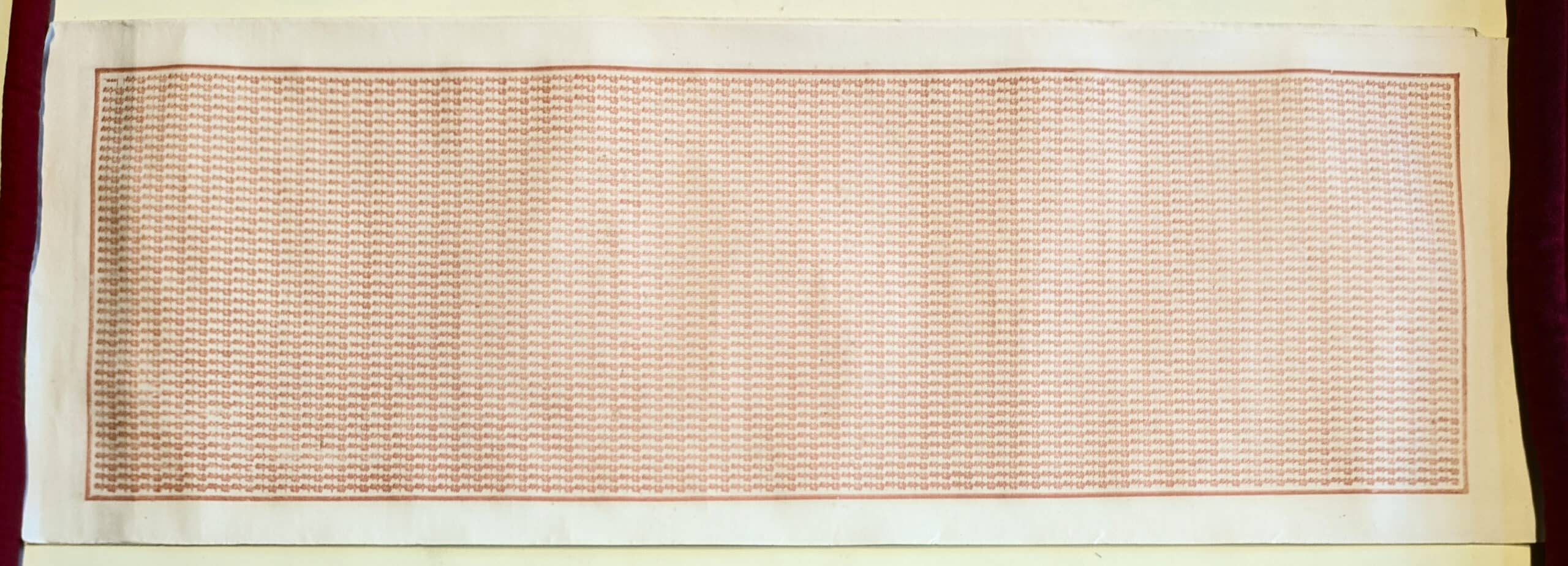

Om Mani Padme Hum mantra scroll printed by Schilling von Canstadt in 1835 in St Petersburg, for use in monasteries in Buryatia.

Om Mani Padme Hum mantra scroll printed by Schilling von Canstadt in 1835 in St Petersburg, for use in monasteries in Buryatia. An important part of BDRC's mission is technological innovation to make the Tibetan language a first-class citizen in the digital world. A major milestone in that enterprise was passed recently, as the open source software suite LibreOffice now supports an important feature of Tibetan: very long paragraphs.

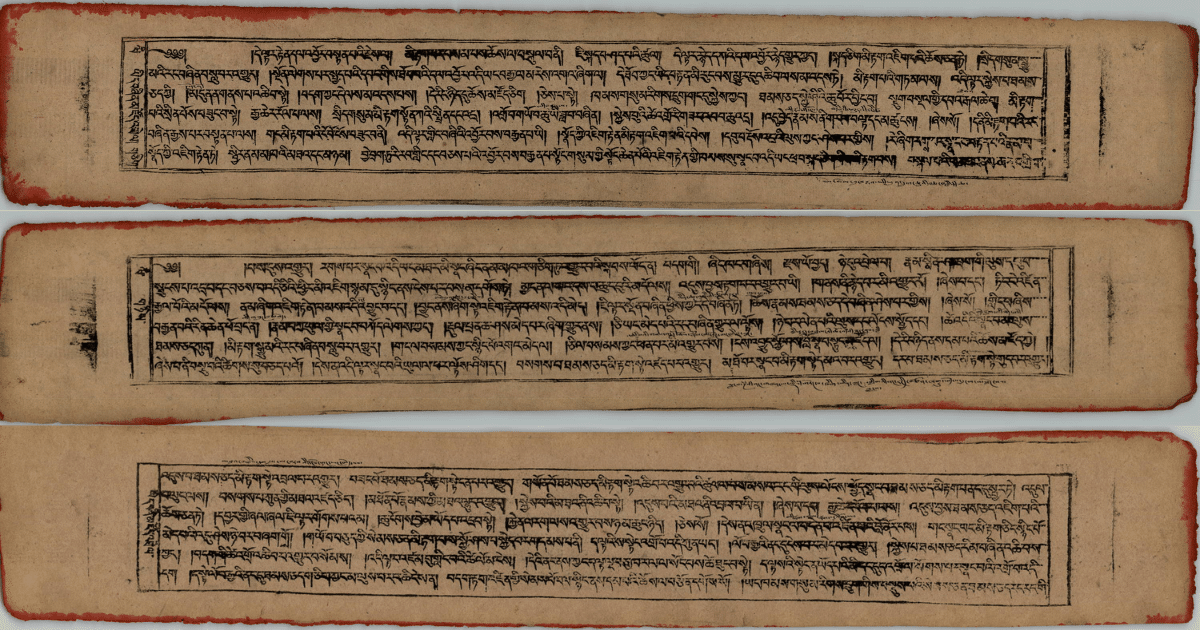

Tibetans have invested tremendous energy and resources into writing, innovation, and technology since the introduction of Buddhism in the eighth century. Many of you will know the story of how the Tibetan script and classical language were invented for the purpose of translating Buddhist texts from Sanskrit (and Chinese) into a language Tibetans would understand. In the 14th Century Tibetans widely adopted the technology of woodblock printing as a means of mass producing the Tibetan translation of the scriptures and also the thousands of volumes of Buddhist texts written directly in Tibetan by Himalayan authors. Fast forwarding to more recent times, the creation of Tibetan computer fonts was a quantum leap in the evolution of Tibetan and its integration in the digital world. Of particular note was the inclusion of Tibetan in the Unicode Standard, the global standard for the codes that underlie computer fonts for all of the world's writing systems.

However, written Tibetan has important features that are still not supported by all tools or applications. One that may be surprising is very long paragraphs: in fact, the typographical notion of the paragraph does not really exist in a Tibetan text the way it does in European languages. As a result, Tibetan texts often need to be processed as a long stream of uninterrupted text with no forced line breaks, sometimes over hundreds or thousands of pages.

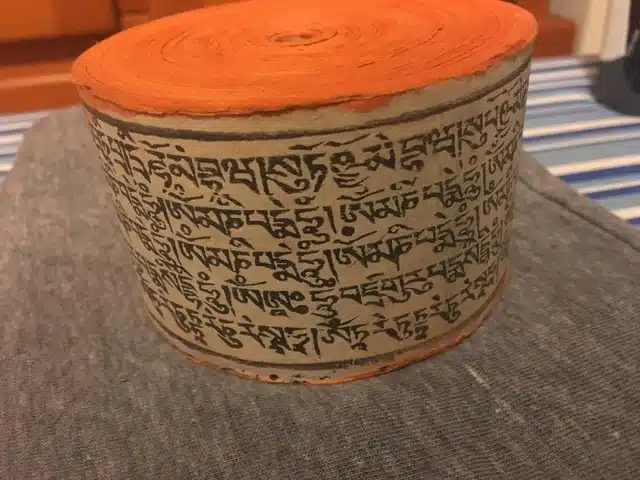

Examples of long Tibetan scrolls of unbroken text that are placed inside prayer wheels.

Examples of long Tibetan scrolls of unbroken text that are placed inside prayer wheels. In general, word processing software programs were originally designed with English text in mind, meaning that they support relatively short paragraphs (possibly up to a few pages), with words separated by spaces that can have a flexible width. These assumptions don't work for written Tibetan, however, where paragraphs are virtually limitless and contain very few spaces. The result is that such a word processor performs very poorly, if it works at all, when opening a long Tibetan text, and it will therefore be impossible to use for any serious publication project.

LibreOffice is one of the only mature and stable open source word processors (i.e. inspired by MS Word) that is available for free on all possible platforms, including Linux. It is relevant to Tibetan Studies and the Tibetan community because it is free and open source, while popular commercial software programs such as Word or InDesign which can handle long Tibetan texts, are expensive and in many parts of Asia often used in pirated versions. So long as LibreOffice could not handle long paragraphs there was essentially no free tool to publish Tibetan.

In 2015, BDRC's CTO, Elie Roux, reported the issue to LibreOffice. Unfortunately an intervention in the code of LibreOffice is a big project that would have required weeks of research and development, and therefore there was no evolution on that front. That is until a few weeks ago, when a developer named Jonathan Clark tackled the issue and fixed it! A long text like Longchenpa's Yishindzö (view on the BDRC archive at: yid bzhin mdzod), which consists of one "paragraph" of 153 letter size pages, now opens quickly and can be edited in LibreOffice. The conversion of the RDF file of this particular text into a PDF used to stall after 45 minutes and it is now completed in 13 seconds! This is a remarkable improvement of several orders of magnitude, something quite rare in software optimization.

A long text like Longchenpa's Yishindzö, which consists of one "paragraph" of 153 letter size pages, now opens quickly and can be edited in LibreOffice. (View on the BDRC archive at: yid bzhin mdzod).

BDRC's modest contribution to this breakthrough is just to have planted the seed many years ago, but we want to acknowledge and rejoice in Jonathan's good work, and the consequent strengthening of Tibetan in open source publication tools!

The support for very long paragraphs was integrated in LibreOffice 24.8.2, released on September 27 2024. We encourage you to try it out and send us comments on your favorite software to edit Tibetan, or the most important shortcomings you experience in this type of tool for Tibetan. Working together as a community, we can continue to innovate and keep Tibetan up to speed with the digital technology of other languages.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.