Tibetan pilgrims during the Kailash kora. By Jean-Marie Hullot from Wikimedia Commons.

Why do Tibetan Buddhists go on pilgrimage? They go on pilgrimage for many reasons but mainly they go to accumulate merit, to grow spiritually, and to engage in a sacred, meritorious, and meaningful activity. They go for blessing and empowerment, and for purification and penance. They also go to grow in their understanding of the world, to travel and expand their knowledge and their horizons. And they go for pleasure, for novelty, for fun, and all the usual reasons that people undertake long and arduous journeys. They go to be transformed. The Tibetan word for pilgrimage is "nekor" or "nejel," meaning to either circumambulate a holy place or to meet a holy place. And to meet the holy place is to be transformed by the holy place.

One of the most interesting genres of Tibetan Buddhist literature is the lamyig text, the travel guide, or more appropriately the pilgrimage guide (a subset of lamyig, called the neyig). These travel and pilgrimage guides are not only the most accessible and useful of texts to a wide variety of readers, but they contain history, geography, biography, philosophy, religion, art and anthropology, and more. We have been collecting, digitizing and preserving these texts for the past two decades, and at this point, it would be fair to say that we have more lamyig texts in our online library than any other library or collection in the world.

In the last one hundred years, perhaps the most widely reprinted and read Tibetan guidebooks were Gendun Chophel's Guide to India and Katok Situ's Guide to Central Tibet. For Tibetans, India is the original holy place. It's the holy land for Tibetans, being the land that the Buddha and Buddhism came from, and the home of most of the Panditas that came to Tibet over the centuries bringing teachings, sutras and tantras with them. But gradually, Buddhism disappeared in its homeland–a key incident being the destruction of Nalanda University by the Turk military general Bhaktiyar Khilji in the 1190s–and the Delhi Sultanate (1206-1526) and the Mughal Empire (1526-18th c) came to rule India. So over the last millennium, with Buddhist India vanishing, Tibetans began to see many places on the Tibetan plateau as essentially equivalent in sanctity to the traditional pilgrimage sites in India. U became the holy place of Tibet, with the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa city the centerpoint of sacredness.

Let's now take a sweeping look at some of the travel guides that have been written by intrepid Tibetan explorers over the centuries, sharing their travels and knowledge with their fellow Buddhists. These guides were no mere armchair reading material; certainly there were people who read them for pleasure and edification but pilgrims also used these guides as practical references when they traveled.

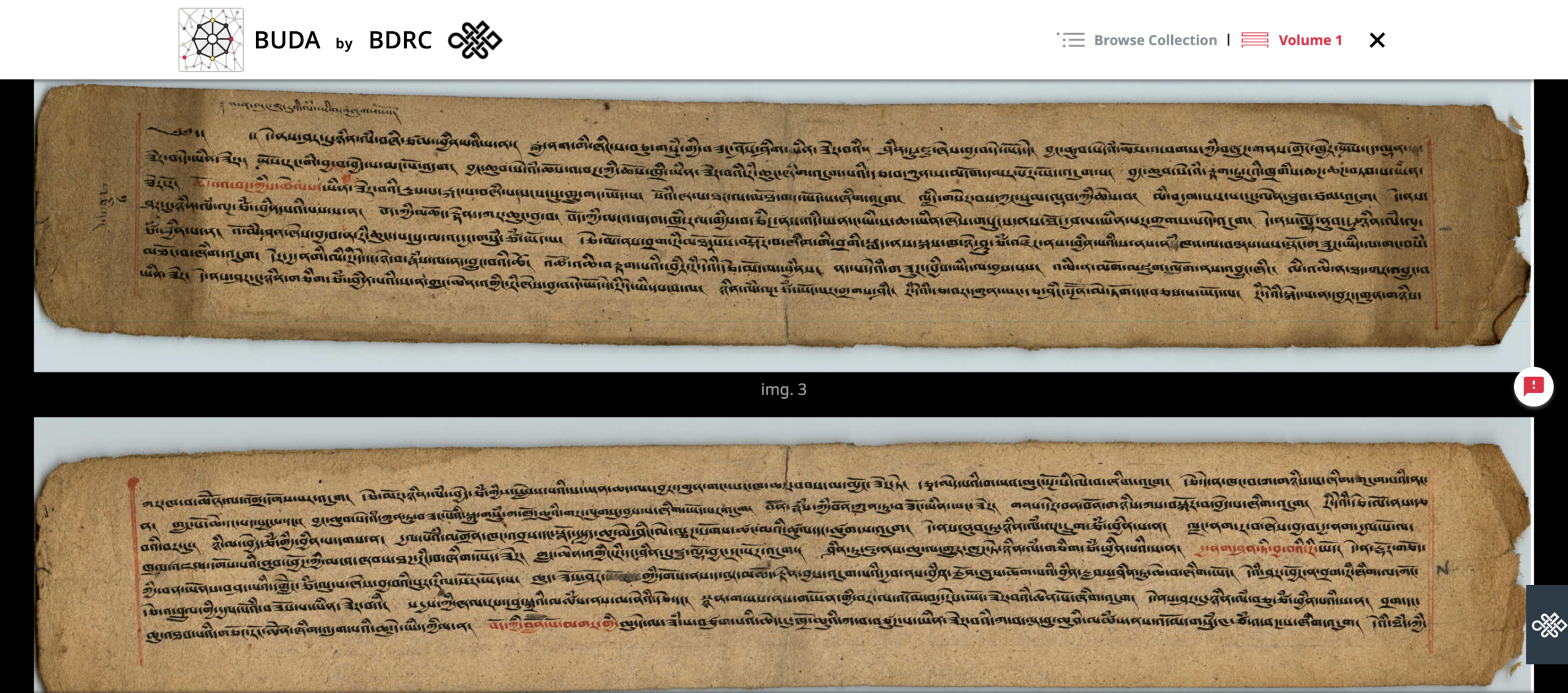

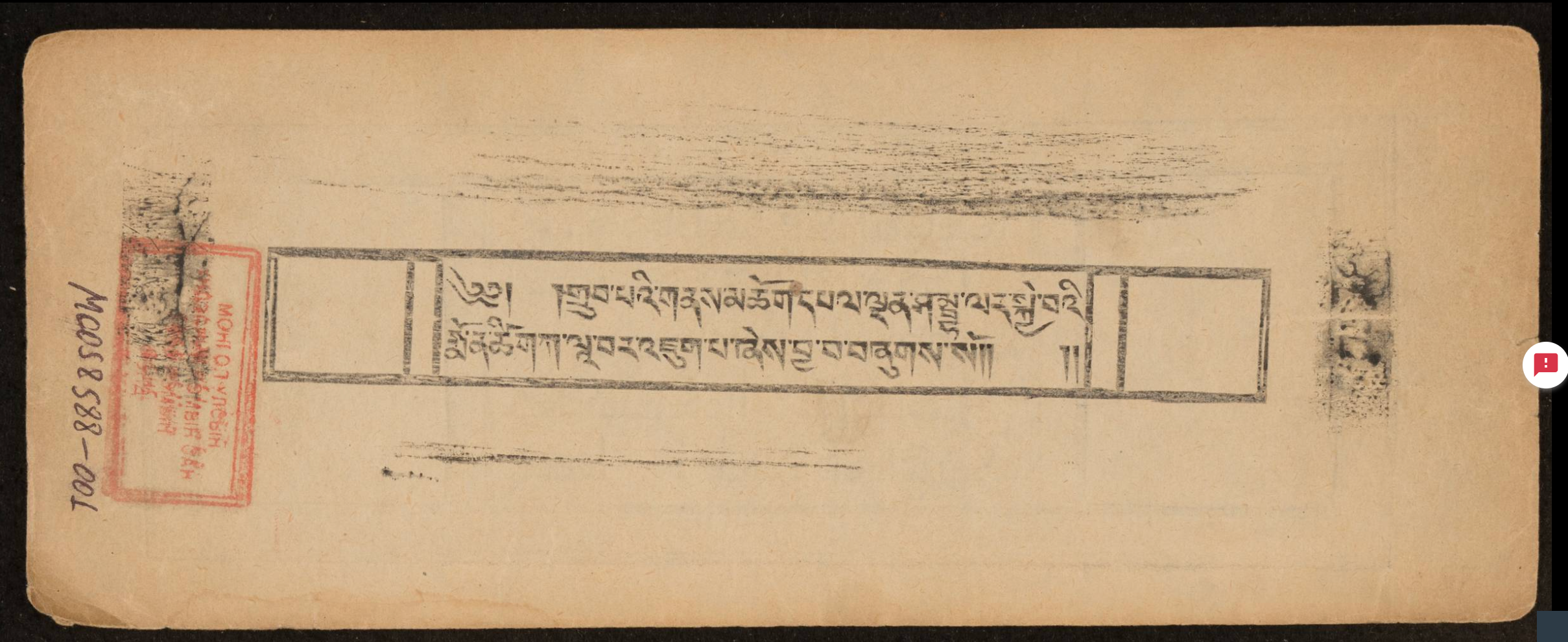

A 13th century travel account to Tibet, India and China, this is one of the earliest Tibetan travel guides. It's by Menlung Sonam Pal (b.1239), an abbot of Menlung Monastery in Gyantse in Central Tibet. Naturally this man, who was a monk, didn't travel the breadth of Asia but at this early date in the evolution of the lamyig genre, Tibetans wanted to invest their holy sites with as much authority as those in neighboring lands with much older and more established Buddhist cultures. The guide is a manuscript of thirty pecha pages. Although it's not very long, it's of great interest as one of the very early examples of this Tibetan genre. This particular manuscript has nice Ume handwriting in black ink with occasional red ink.

Another of the oldest Tibetan travel guides is by Nyo Gyelwa Lhanangpa Sangye Rinchen, another monk, about the sacred place of Tsari. He came from a wealthy family; his great grandfather had been Marpa's traveling companion in India, and Sangye Rinchen himself longed to travel to India. Instead he became a monk at Drikung Til, spent years in retreat at Tsari, becoming very familiar with its sacred landscape and sacred mountain Dagpo Shelri, the Crystal Mountain. He ended up writing the guidebook to Tsari which soon became established as an important (if rather dangerous and remote) pilgrimage site. Sangye Rinchen was founder of a sub-branch of the Drikung, so it makes sense that Songtsen Library has reprinted this book.

Pilgrimage Guide to Riwo Tsenga (Wutai Shan)

Changkya Rolpai Dorjee (b.1717-d.1786) was the principal Buddhist teacher at the Qing court in the 18th century. He was the Qianlong Emperor's main Tibetan translator, tutor, and National Preceptor, and importantly, an intermediary between the Qing Emperor and Inner Asia. In between his diplomatic work, he also found time to write a Guide to Wutai Shan, describing the Buddhist sites and temples there. Wutai Shan means Five Terraced Mountain and is considered to be the home of Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom. Changkya's knowledge of Wutai Shan was important in other ways: he played a significant role in the founding of Yonghegong, the monastic college for Mongol, Manchu and Chinese monks in Beijing. Like Wutai Shan, Yonghegong was both an imperial palace as well as a Buddhist monastery. Unlike India, which is full of sacred sites for Tibetans, China doesn't capture the Tibetan Buddhist imagination in the same way, but this Guide helped to establish Wutai Shan as an important pilgrimage destination for Tibetans.

Written by the Sixth Panchen Palden Yeshe in 1775 at Tashilhunpo Monastery, this guide expands the genre of lamyig and is well-known in Tibet. In the Tibetan Buddhist world, travel and pilgrimage guides don't always lead to mundane and worldly places. Sometimes they are accounts of mystical and fantastical journeys, or guides to hidden lands known as "beyul" accessible only to the very fortunate few. This is a prayer to be reborn in Shambhala, which is just another means of "traveling" to a holy place, that was based on visionary experience and previous guides to Shambhala.

This was written in the 1850s by Jamyang Kyentse Wangpo, one of the most prominent lamas of the 19th century, and if another prominent lama, Jamgon Kongtrul, had not sought advice from Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo, this text might not have been written. Indeed, this famous guide likely originated in response to Jamgon Kongtrul's request, on the eve of his own travel to Central Tibet, for a list of holy sites to visit. Khyentse's Guide is a simple and short work, consisting mainly of a list of places to visit. Many of these lamyig are only available in Tibetan language, but Matthew Akester has translated Kyentse's Guide to Central Tibet into English.

Image from Khyentse Foundation's site.

Pilgrimage Guide to Utsang/The Travel Diary of Katok Situ

Written by Katok Situ Chokyi Gyatso (b.1880) during the years 1918-1920, this text gives a detailed and exhaustive listing of the temples in Central Tibet. Katok Situ not only describes what he saw at all of these sites, he also describes the contents of the temples and the monasteries. He would have used the travel guides of monks and travelers before him, and particularly the travel guide of his uncle Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo, just as his own travel diary became useful to those who came after him. His detailed accounts of the interiors and contents of the pilgrimage sites were particularly useful, producing a snapshot in time of former treasures of these sacred sites, most of which were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution.

This famous guidebook, written by the intrepid Chinese Buddhist monk and explorer in the 7th century, only became available in Tibet in the 18th century. It was translated by Gonpokyab, and since its translation, has become very popular among Tibetans as indeed it has become around the world. Xuanzang describes an epic pilgrimage across a swath of the globe, traversing from Xian all the way through the deserts of Central Asia and through the heart of India. It is his descriptions of Nalanda University that have helped us understand the importance and the significance of Nalanda before its destruction.

Gedun Chophel's Guide to the Pilgrimage Sites in India

Gedun Chophel's guidebook is perhaps one of the most useful of the guides to India, since it's full of practical advice and information regarding railway connections, proper distances etc in addition of course to the sacred histories of these places. Indeed he spent a significant amount of time in India, learned the language, mingled with the locals, and traveled widely. One of the most famous 20th century Tibetan figures, with writings that are beloved by Tibetans all over, Gedun Chophel wanted his fellow Tibetans to modernize, innovate, and to catch up to the 20th century. He thought they should learn more about the modern world, and this travel guide was one of his attempts to expose Tibet and Tibetans to the wider world. It's a testament to his enduring influence on the Tibetan psyche that Tibetan pilgrims from Tibet and elsewhere even today use this guide when they go on an Indian pilgrimage.

Of course, this is not an exhaustive list of the travel and pilgrimage guides in our vast archive. We encourage you to explore our list of travel guides HERE. As your summer travels and vacations come to an end and fall approaches, we suggest some light and cosmopolitan armchair travel in the Buddhist world!

Outer pilgrimage circuit around Katok Monastery, Derge, Kham.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.