The site was down. That's how Chris Tomlinson first became connected with Gene Smith and the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center in 2000. She was a computer programmer, hacker and researcher at Sun Microsystems. She had put herself through college by working as a computer operator, and even worked on automating polygraph lie detectors. Born in the Episcopal church, Chris first came across Buddhism in college, where she read Nagarjuna's Fundamental Verses on the Middle Way and Alexandra David-Neel's books about Tibet. Now, she was rediscovering Buddhism after rediscovering herself.

Chris had transitioned gender ten years earlier, reincarnating herself as a woman. "I decided to just try and be who I thought I was," she says. "Life for animals and humans is largely a scientific experiment. We are all scientists in one form or another. We are all just collecting data." In this case, the data was clear, and Chris transformed her life.

Of that period, she says, "It was easy and it was hard," a very Buddhist statement. In 2000 when she came across Gene's brainchild, tbrc.org, she was fascinated. She learned some Tibetan and she kept reading, relying on TBRC to access Tibetan texts. Then one day when the site was down, she called the office (with a number gleaned from Internet Archive's Wayback Machine) and Gene Smith picked up. The rest, as they say, is history.

Four years later, by 2004, Gene had recruited Chris to the cause and she was now working with Jeff Wallman (TBRC's then Director of Technology and later Executive Director) to build the new TBRC library, which would become tbrc.org. The new tbrc.org library system allowed multi-user cataloguing, which was a major enhancement. The original site launched in 1999 was a single-user ASK SAM database (a desktop system) that allowed only Gene to catalogue. Now, with the XML system, it was possible for Gene and his librarian corps to collaboratively create in-depth outlines and catalogues for the breadth of Tibetan literature, their work rivaling any existing catalogue, including that of the U.S. Library of Congress.

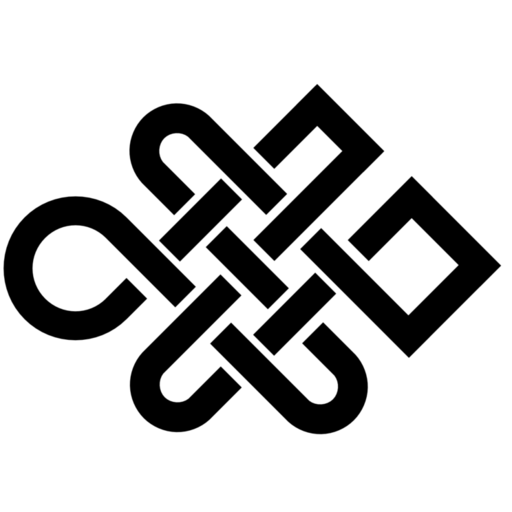

In the back row, left to right: Former BDRC Executive Director Jeff Wallman, Robert Chilton, BDRC's Technical Lead Élie Roux, and BDRC's Senior Technologist Chris Tomlinson. In the front: Emma Lewis, Peter Le Blond, Mrs. Peter Le Blond, and Jerry Barrett. Photo taken at Harewood House in Yorkshire.

In the back row, left to right: Former BDRC Executive Director Jeff Wallman, Robert Chilton, BDRC's Technical Lead Élie Roux, and BDRC's Senior Technologist Chris Tomlinson. In the front: Emma Lewis, Peter Le Blond, Mrs. Peter Le Blond, and Jerry Barrett. Photo taken at Harewood House in Yorkshire.After Chris had tbrc.org up and running, Gene needed her for another important task. Gene's first thought was always access and dissemination, and he wanted to make sure that the Tibetan monasteries had the entire archive on a disk. A master drive of the archive was created. David Lunsford, TBRC board member and the man who had convinced Gene to digitize, set off on a monastic tour, with Chris providing the essential technical support. They were Gene's representatives, delivering precious texts to the monks and nuns who needed them.

From Dodrupchen Monastery in Gangtok to Tibet House in Delhi to Palyul Monastery in Bylakuppe, they brought copies of the archive to lamas and abbots across the Indian subcontinent. In Bhutan, they gave one copy to the National Library of Bhutan. At the Tashichho Dzong, the seat of the Bhutanese government, they installed a drive in a printing house right by the Dzong so that the monks could print the texts directly from the drive. It was an auspicious trip. On their return, they met with Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche who was consecrating a stupa at the Chukkah power station and they had lunch with Rinpoche. The power stations were necessary. Electricity kept going out throughout their trip, ruining the disks but somehow Chris managed to make copies of the master disk all along the way.

They skipped Nepal on the tour because of the Maoist insurgency but, as it happened, Chris ended up moving to Nepal in 2006 where she stayed for the next seven years. Living and working at Palyul Retreat Center in Pharping, she also set up, in consultation with Gene and Jeff, Palri Parkhang Software, training people to use image processing in the service of Tibetan Buddhism. Chris and the Palri Parkhang team digitally restored selected texts from the TBRC archive, so that they can be printed for textbook use in monastic curricula. Wedded to the mission of TBRC, she continued to maintain the tbrc.org library.

Palri Parkhang in Kathmandu. Dorje Choedon, Chris and Gen la, office manager at Palyul retreat center.

Palri Parkhang in Kathmandu. Dorje Choedon, Chris and Gen la, office manager at Palyul retreat center.She explains, "I was committed to the mission statement, which is to preserve, make accessible and disseminate a body of Buddhist textual materials, from the Buddhavacana to the great commentarial materials. Tibetan culture is certainly a culture of the book, and books are sacred and to be treated with reverence. It's a bibliophile's culture. And that's how I have thought of it. It's what some people call an enlightenment project."

At Palyul, Chris maintained the audio systems for the retreat center. She also built the generator and inverter systems to keep the electricity running for her teacher Khenpo Namdrol Rinpoche and all the retreatants. This was no small feat in Nepal, famous for its so-called load-shedding—at peak load shedding periods, the lights went out for over 16 hours a day. People needed light. Her work at Palyul Retreat Center, like her work at TBRC/BDRC, was quite literally an enlightenment project.

Chris calls herself "a sort of Buddhist." She doesn't quite believe in a singular consciousness or reincarnation. She says, "What I do believe in is that our actions and interactions throughout our lives influence future lives. My interactions with other BDRC staff and with the users of tbrc.org—it becomes a giant web of interactions, and that web is conscious."

Chris's conscious web of life is very like the library itself that she helped build: a vast and expanding universe of Buddhist texts expressing Dharma, which is wisdom and life itself. Her work building tbrc.org and now BUDA (the Buddhist Digital Archives, BDRC's new library platform and a reincarnation of tbrc.org) is a perfection of generosity as luminous as lighting a lamp in the dark, or rather, turning on the generator. After all, the library itself is a generator, of Dharma.

The library going dark is what brought Chris to BDRC. Since that time, she has been the one ensuring that the library would never go dark for anyone else.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.