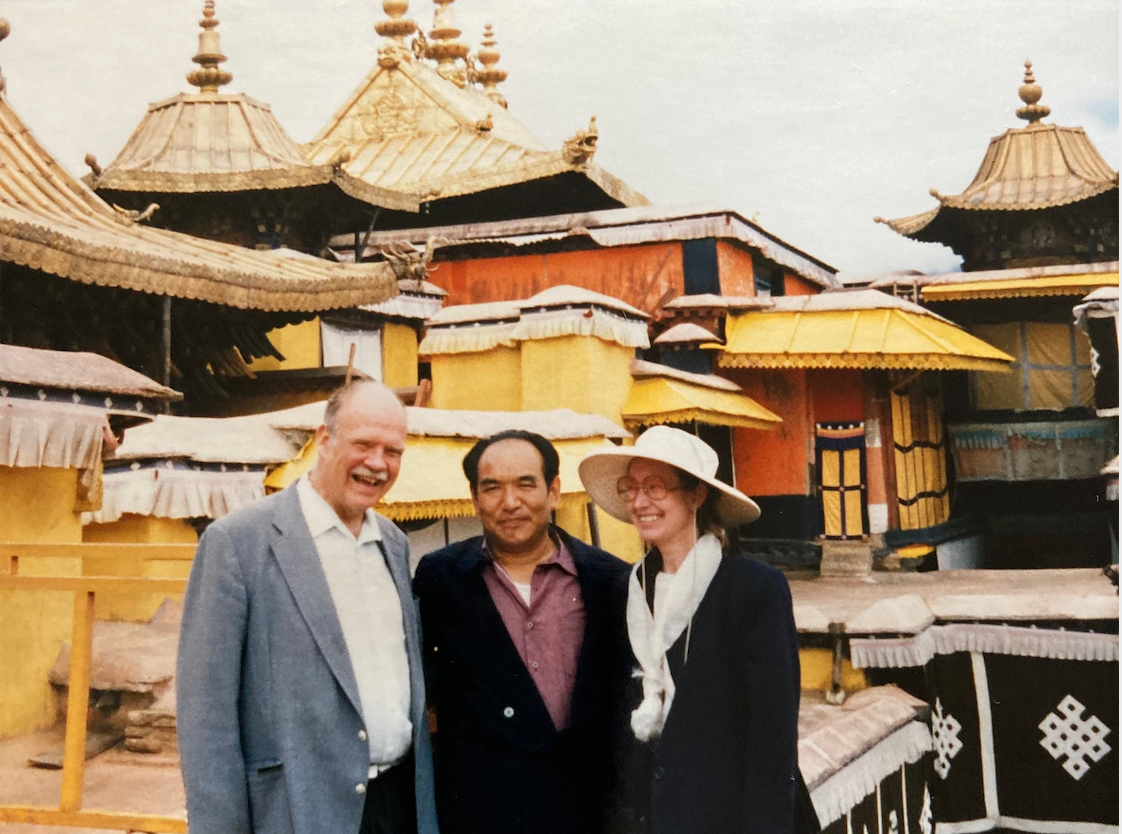

Susan Meinheit with BDRC's founder Gene Smith and Dawa Tsering Lukhang, Director of Research at Potala Palace, on the roof of the Potala, Lhasa, 1997. Personal photos courtesy of Susan Meinheit.

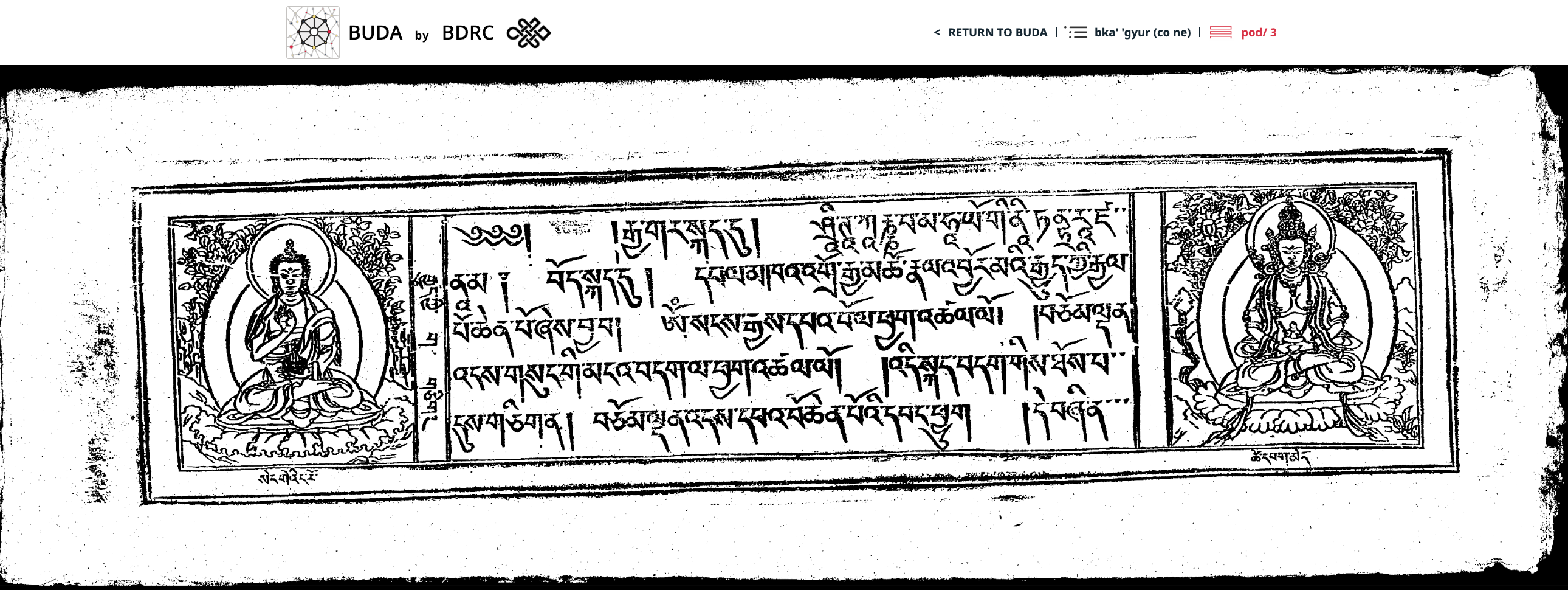

The Buddhist scriptures had been left in storage for so long that the pages had melded together and the volumes had congealed into bricks. For months, Susan Meinheit, the Tibetan Librarian at the US Library of Congress, had spent two to three hours every day separating the pages slowly, gently prying apart each folio one at a time. Each page, which itself was made up of several sheets of very thin paper, had to be coaxed carefully away from its neighbor.

"I was told the paper was poisonous," Susan recalls, "I would get very dizzy and my fingers would get numb. But eventually, we finished it and we microfilmed it." It was the only known complete copy of the Chone Kangyur in the West, a rare set of the Tibetan Buddhist canon. "It was like a blessing to go through this, folio by folio, of this precious precious text. The print was so clear. Just to sit and work with that text was a delight."

The Library of Congress's collection of Tibetan Buddhist texts began with the gift of 57 Tibetan woodblock prints and 8 manuscripts in 1901 by William Woodville Rockhill, an American diplomat and the first American Tibetologist. This gift was the foundation of the Library's spectacular Tibetan Collection, now one of the largest in the West with 17,000 monograph volumes, 3,600 volumes of rare books, and thousands more texts on microfilm. But for three quarters of a century, the collection was neglected, with new acquisitions placed in deep storage in book cages and forgotten.

- {%CAPTION%}

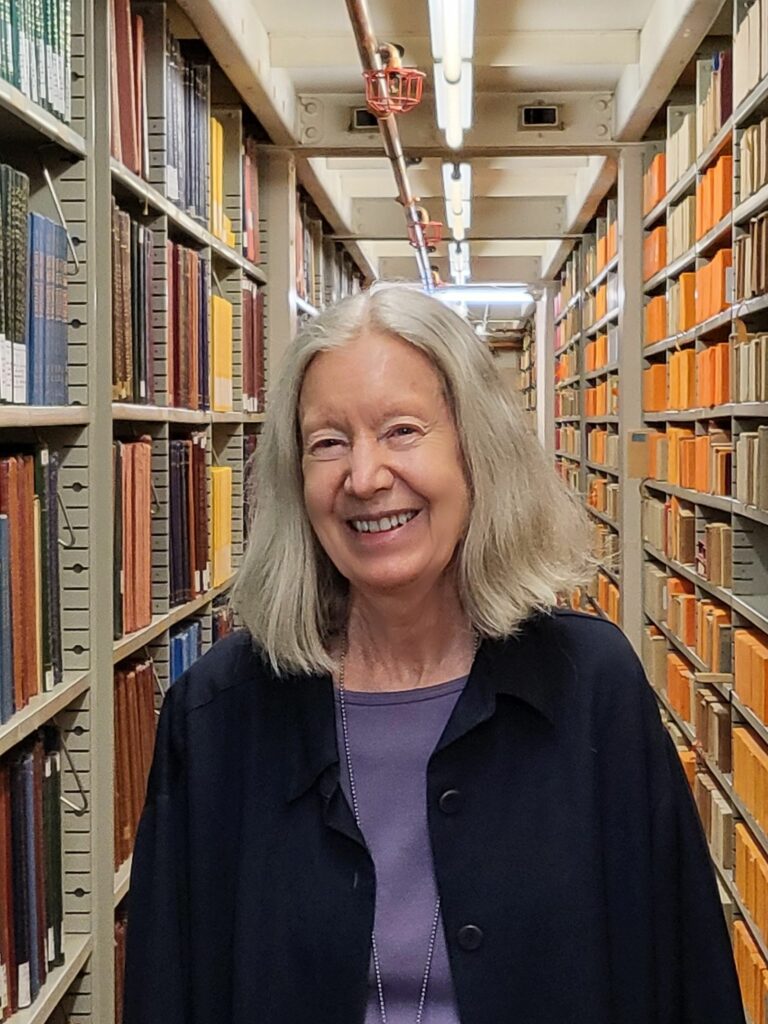

When Susan Meinheit, whose official title is Tibetan and Mongolian Specialist at the LOC, started working at the Library as a clerk in 1975, the position of Tibetan Librarian did not even exist. It was a role she would go on to create. With her mentor and colleague, the legendary scholar E. Gene Smith, she would shape and define the Library's Tibetan collection.

Susan's interest in Tibet started young. A child of the fifties in small-town Illinois, Susan grew up reading National Geographic and Life magazine articles about Tibet and remembers watching newsreels about the Tibetan uprising in 1959. Her favorite comic book was Mickey Mouse in High Tibet, her favorite novel Lost Horizon. Tibet captured her imagination wholly as a remote and exotic place.

Working at Florida State University Library after college, she audited a World Religions class. On the syllabus was the short documentary Requiem for a Faith, which depicts religious practices of Tibetan Buddhist society. The film affected her profoundly, especially the debate scenes of the monks practicing their daily Buddhist debates.

She said, "I realized this was a living thing; it was not a remote unreachable fantasy." Indeed it wasn't a fantasy at all. When she saw a video of Tibetan refugees carrying precious religious texts over the Himalayan mountains, she understood that the Tibetans who had lost their country were working hard, against all odds, to preserve their culture and reestablish their monasteries and institutions in India and Nepal.

She wanted to be a part of that effort—the caretaking and the rebuilding of Tibetan culture. A friend told her about the LOC's neglected Tibetan collection and Susan decided that she wanted to take care of it. At her job interview, when she was asked why she wanted the job, she said, "Because you have the best Tibetan collection in the world, and I want to do something with it."

At the Library, Susan started teaching herself Tibetan with Bell's Grammar of Colloquial Tibetan. A colleague who saw her studying Tibetan in the break room told her she must meet another LOC staffer, who just happened to be on home leave at the time. And so she met Gene Smith.

A beautiful 17th century manuscript of ʼPhags pa bskal pa bzaṅ po pa źes bya ba theg pa chen poʼi mdo, from the LOC's Tibetan Collection.

Gene Smith, the founder of Buddhist Digital Resource Center, was working in the LOC's Delhi field office at the time, and became Susan's mentor. Although in a sense, he already was her mentor even before they met. Susan was studying Gene's famous introductions to the texts he acquired for the LOC, typing them up in order to learn from them. Gene was delighted to have a Tibetophile working at the home office. After all, the Tibetan texts he sent the Library from India were just collecting dust in yellow baskets. At the time, no one at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. could even read Tibetan.

It was clear to both Susan and Gene that the Tibetan collection needed a curator and caretaker and that this person was now going to be Susan. Susan began formal Tibetan language classes with Geshe Tharchin (former Khenpo of Sera Mey monastery), who was living at the Buddhist Vihara on Sixteenth Street on a sabbatical sponsored by a NASA scientist. There were six students in the class, including the LOC's Burmese cataloger, someone from the Department of Transportation and a FEMA employee. She was to continue studying with him for the next 29 years, both in Washington and in the Kalmyk Mongolian community in New Jersey.

Gene took the "trial by fire" approach to teaching Susan, asking her to hunt for texts contained within the Library's vast repositories, texts no one had seen but Gene knew were there. For instance, Gene asked her to find a list of sungbum that the explorer Joseph Rock had collected from Yunnan and deposited with the Library. In the intervening decades the texts had disappeared deep into the massive book cages of the library but luckily, Rock handwrote a list for Gene. It took Susan years but she finally found 57 of the 64 volumes. These included rare works by, among others, the Second and the Fifth Dalai Lamas, the Panchen Lamas, Yongzin Yeshe Gyaltsen, Pema Karpo, and Drukpa Kunley.

Another time, Gene asked her to look for Khotanese manuscripts in the book cages. He had been reading Oscar Terry Crosby's Tibet and Turkestan: A Journey Through Old Lands and a Study of New Conditions, and learned that Crosy had found rare Khotanese manuscripts for the Library. Where were they? Susan found them in the Tibetan Rare Book Cage, in a dusty old manila envelope that still held a blanket of dust and sand from the Taklamakan desert. Inhaling the cloud, Susan promptly got sick, but she had surfaced invaluable and long lost Khotanese fragments.

- {%CAPTION%}

Gene sent her on wild goose chases through the Library's holdings, and he sent her scholars with complicated research questions to untangle. Susan learned by investigating, exploring, reading, and discovering. Before starting at the LOC, Susan had worked briefly for an underwater archaeologist who searched for sunken Spanish ships off the Florida Keys. Now she was the treasure hunter, or more appropriately, treasure revealer (terton), surfacing invaluable texts from deep within the richest reservoir of books in the world. Whenever Gene came back to DC, Susan and Gene explored the cages together. "I couldn't have found a better teacher," said Susan.

Susan continued her education in other ways, taking evening classes and receiving her Master's in Library Science from Catholic University. Her promotion to the Asian Division now meant that she and Gene were working even more closely together. She became so indispensable that eventually the Library created the Tibetan Librarian position for Susan, who was already doing the work because of her passion for these texts.

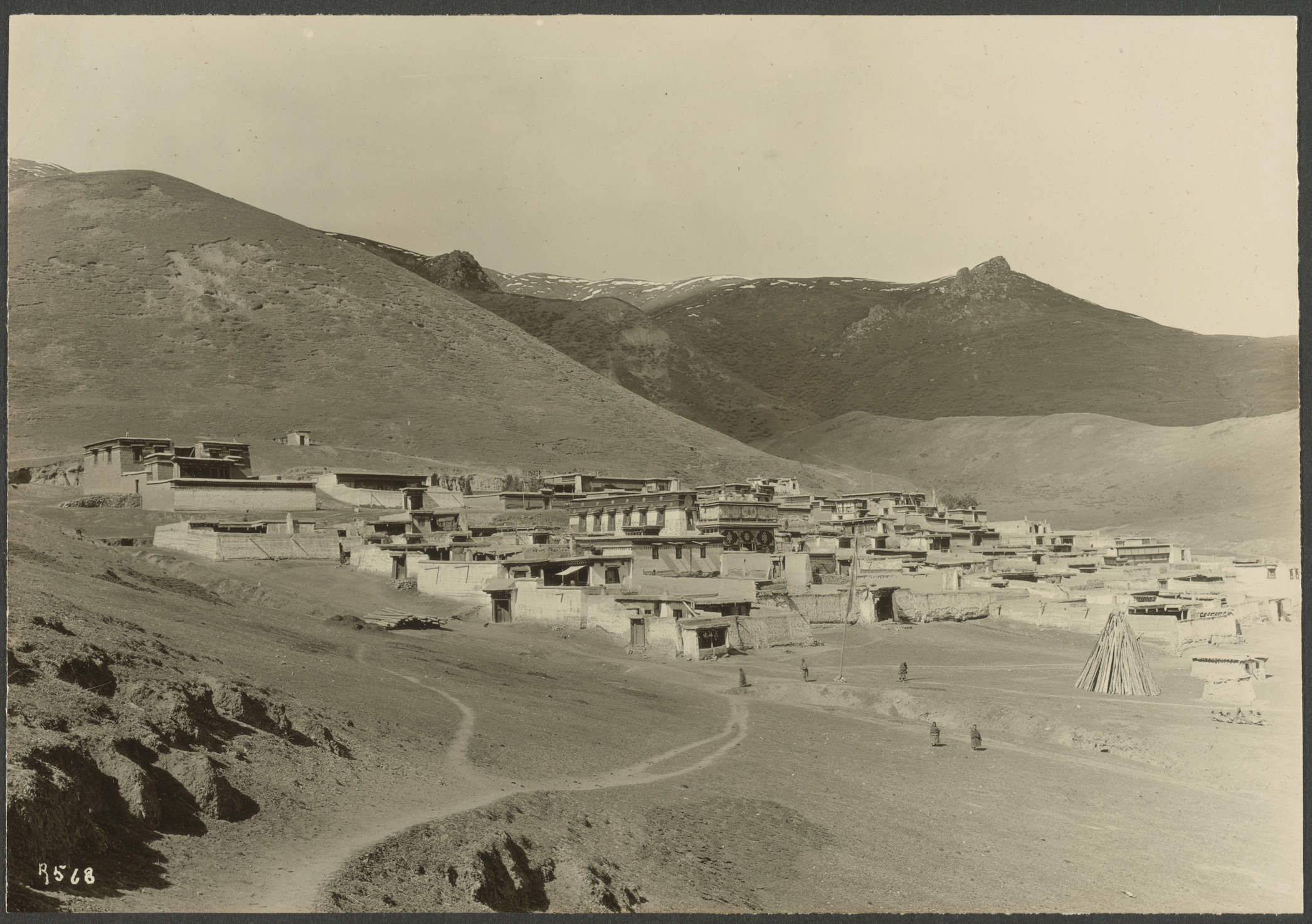

Chone Monastery in 1925. Photograph taken by explorer Joseph Rock. Courtesy of Arnold Arboretum Library, Harvard University.

The Chone Kangyur and Tengyur, that rare set of the Tibetan Buddhist canon, is a case in point. The LOC copy, the only complete copy of the Chone Kangyur in the West, had been purchased for the Library by the explorer Joseph Rock in 1926. Of course it was Gene who asked Susan to look for it—the Pedurma (dpe bsdur ma) Publishing House wanted to reprint the canon, and Gene also wanted to include it in his new digital library at Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center (now Buddhist Digital Resource Center). The Tengyur and five volumes of the Kangyur had been microfilmed in 1955, but where was the rest of the canon? When Susan finally found it, the volumes, almost three hundred years old at that point, were in bad shape with the pages sticking together as if they'd been glued. With patience and care, her fingers numb from the toxic paper, Susan rescued the Kangyur, all 108 volumes of it. She had gotten to the texts just in time.

Afterwards the LOC microfilmed the Kangyur, and sent copies on CDs to both Gene and the Pedurma Publishing House, which included it in their comparative edition of the canon. The Chone Kangyur and Tengyur is now one of the Tibetan Collection's highlights at the LOC. The canonical collection can also be accessed through BDRC's online library.

The Chone Kangyur in BDRC's archive, scanned from the microfilm provided by the Library of Congress. BDRC Resource ID: W1PD96685.

One of Susan Meinheit's first major initiatives as the new Tibetan Librarian was to get New Delhi to restart the Tibetan text acquisitions program that had begun under the PL-480 "Food for Peace" program. The Tibetan text acquisitions program had ended in 1985, and in 1987, Gene, who was overseeing the program, left New Delhi for Indonesia. After a visit to the LOC's collection by HH the 41st Sakya Trizin, who commented on new publications being made in Tibet, Susan realized that in the years since the end of the PL-480 program, there had been a renaissance in Tibetan publishing inside Tibet.

- {%CAPTION%}

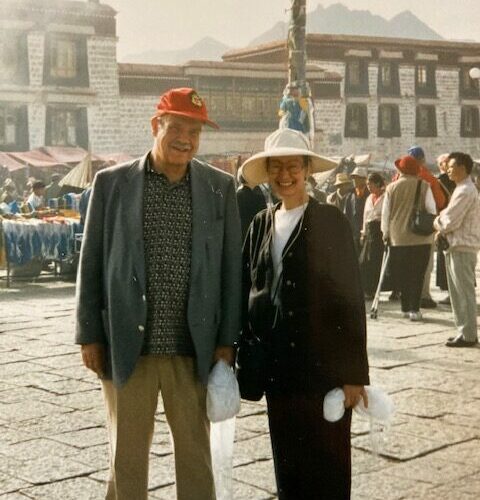

Her first book acquisition trip to Tibet, the first of four, took place in 1991. Invited by the China Tibetology Center in Beijing, she gave a paper on the Tibetan collections at the library, making the case for information exchange and the preservation of Tibetan literature. She also went to Mongolia, hosted by the state publishing house, to assist the New Delhi Field Director in establishing the Mongolian text acquisitions program. When Susan returned to Tibet in 1997, Gene came with her. They went to Lhasa, Shalu, Sakya and all the other places and printing houses that they knew from their books. "It was amazing to travel with Gene," Susan said, "because he would say, 'Up there is a monastery' and just go into its history and from down on the road, we could barely even see it. He really loved it and they really loved him." Gene, who had never been to Tibet before, knew the place intimately simply from his studies.

Scholars and lamas throughout Tibet knew and loved Gene. As the architect of the PL-480 Tibetan text acquisition program, Gene was the central figure responsible for finding a way to use U.S. government funds to support the preservation of endangered Tibetan Buddhist literature. Working with the Tibetans, Gene saved thousands of texts that would otherwise have been lost.

Now some of these rescued texts were making their way back to Tibet. As Susan said, "Interestingly, some monasteries in Tibet were re-carving lost wood blocks using the Library's photo-reproduced texts of the PL-480 collection, and others were reconstructing their printing libraries."

Decades earlier, it had been the image of the Tibetans carrying their precious texts over the Himalayan mountains that had inspired Susan and now here she was, with Gene, watching the preservation and renewal of Tibetan Buddhism in its heartland.

Susan's career exemplifies the importance of curators and maintainers: the people who do the sensemaking and caretaking that sustains our world. Without librarians like Susan, libraries would be little more than warehouses of books. At the Library of Congress, she gave life to the Tibetan collection, shaping and defining it into one of the most valuable collections at the Library. Because of her, what began as unidentified texts collecting dust deep in storage is now a treasure that draws researchers from all over the world.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.