A photo from Digital Dharma: Recovering Wisdom, published by Wisdom Publications in October 2022.

A photo from Digital Dharma: Recovering Wisdom, published by Wisdom Publications in October 2022. Dafna Yachin is the indomitable director of Digital Dharma, the documentary, and now co-author of Digital Dharma: Recovering Wisdom, the companion photo book. Her deep friendship with our founder Gene Smith (1936-2010), who became her mentor, is what drove the first project. Who else would have chosen to make a movie about a librarian? But Dafna knew, as she said, that he was the Indiana Jones of the book world. And she fell in love with the culture and the people of Tibet. Digital Dharma is the beautiful result of a collaboration between Dafna and her longtime creative partner and close friend Arthur Fischman, her co-author on both the movie and the book. Neither project would have been possible without the key support of Patricia Gruber.

Q: Tell us about you. Can you give us a bit of personal background information?

A: I have been a television and film commercial director since I can remember. I worked for the networks for a number of years, for CBS, for SyFy etc. Then I became a commercial director. It was lovely to be a commercial film director for a while because not many women were film directors back then in the 90s. But I really missed the more thoughtful and compassionate and important story-telling. Because I wanted to do more storytelling with our company Lunchbox Communications, I begged our partners to do more storytelling, more indie films.

Dafna Yachin. Photo by Robert Carter, of Robert Carter Photography.

We had some great stories that we wanted to tell. But it was very difficult to sell to the networks, you had to really know somebody. At the same time, I was doing a lot of nonprofit work, working in justice and women's rights. I was doing work for one of the oldest women's rights groups in the country. I did the Philadelphia Liberty Medal for almost twenty years. So we worked in justice and women's rights. I have always been interested in cultural preservation.

And I was also working with Patricia Gruber and the Gruber Foundation. When I was working with Pat Gruber and Gruber Foundation, on marketing and branding for the foundation before it went to Yale, that was when I first met Gene Smith, at a video interview for the foundation. Later at a Gruber Foundation event, I was seated next to him, and I just found him so fascinating. It was Pat who told me all about what he was doing with BDRC.

Dafna Yachin with her writing partner and co-author Arthur Fischman. Photo by Robert Carter.

Q: So it was Patricia Gruber who made the connection between you and Gene, that first connection that then sparked the film. Tell us more about this meeting with Gene.

A: I think I first really got to know Gene at the Gruber event where I was seated next to him. I still think Pat planned it, you know. And the couple of times I met him, it was so lovely to talk to him. And it was fascinating. Because he would say, oh we just found out that in the Library of Congress there are all these books that were just sitting there, undigitized, and there were these rare texts.

He was like a scholarly Indiana Jones. I kept picturing this Indiana Jones of the book world, as he was telling stories about finding his next treasure of the undigitized books.

Afterwards I told Pat that I sat next to this incredible scholar, and she began to tell me about Gene and his organization, the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center [now Buddhist Digital Resource Center] which he founded, and how they met and how she and Peter were working with him. And of course Peter Gruber has such a history with Tibetan literature, with sponsoring the first English translation of Milarepa, one of the first translations of a Tibetan book into English in the United States. Gene had just moved into the Rubin Museum, which wasn't a museum yet, it was still Barney's and it was being transformed into the museum. In the dressing room, they had stacks of Gene's books that he had collected from India and brought with him.

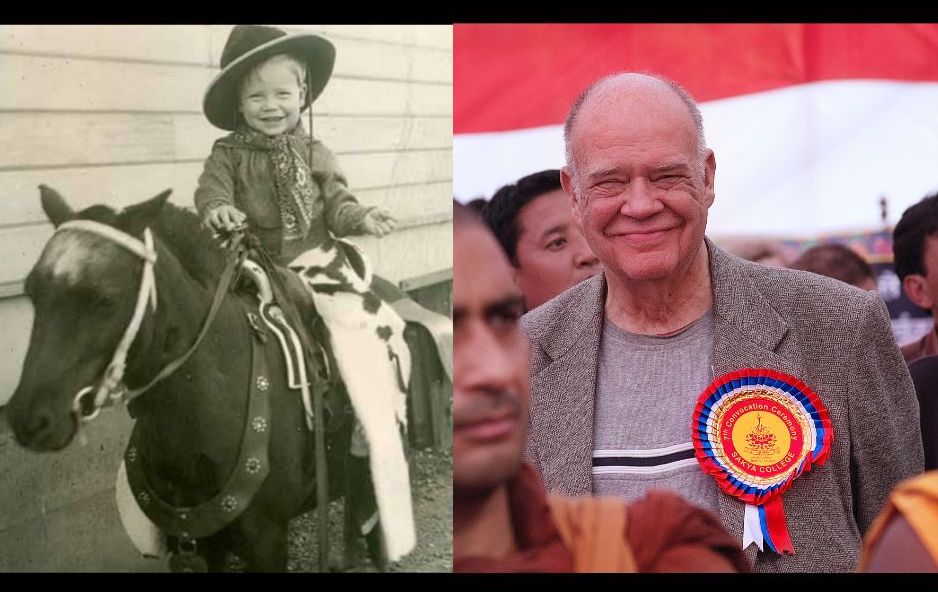

Gene Smith as a boy growing up in Utah & Gene at the Sakya Convocation Ceremony in 2008 in Lumbini, the birthplace of the Buddha. Photos from Digital Dharma: Recovering Wisdom.

Gene Smith as a boy growing up in Utah & Gene at the Sakya Convocation Ceremony in 2008 in Lumbini, the birthplace of the Buddha. Photos from Digital Dharma: Recovering Wisdom. Q: So when you asked Gene about doing the film, he didn't want to do it at first? How did that go?

A: Gene didn't really want to do this. He just didn't seem interested. He was very humble. He always said, 'We are not the actors, we are the facilitators, to help people do things.' We kept pressing him and he finally said yes. We kept saying this is so interesting… he was about to go back to India to deliver the first group of drives, on Apple drives, on which were a collection of 20,000 texts. They were about the size of a small pizza box. And Gene was very pleased and excited to go back to India to bring these texts back with him.

So when I asked again to see if he would let us follow him to make a film, he wrote to me to say, 'Yes, I think that will be okay. We are going back in December, you can work out the details with Jeff [Wallman] about coming back with us.' Tamela, who was one of the producers at the time, and I found crew in India and Asia. Our DP Wade Muller came from Thailand. People loved the project–we were getting a good DP saying they were willing to reduce their rates.

We got grants from the Mellon Institute. We got a grant from the Rubin Foundation, from Shelley and Donald Rubin. We got grants mostly because people loved Gene. We raised enough grants from wonderful people to go the first time. We still weren't sure why Gene let us come. A few days before we were setting off for India, Gene said, 'Hey, can you send up one of your production assistants? I have some things that I want you guys to take with you.' So we sent up Danielle, one of our PAs and she comes back with a roll cart of these Apple Drives… all these boxes! How were we going to take all these in our carry-ons with all our clothes? So we had to repack, take out our clothes and put these drives into our carry-ons and in our backpacks. Tamela and I looked at each other. Now we absolutely knew Gene let us come. He needed people to carry these drives!

Dafna and the Digital Dharma crew filming at Menri Monastery, the monastery of Gene's dear friend Menri Trizin, in north India.

Dafna and the Digital Dharma crew filming at Menri Monastery, the monastery of Gene's dear friend Menri Trizin, in north India.Q: What was India like?

A: This was in 2008, so it was the big crash of 2008. We spent two weeks with Gene in India. We started in Delhi, and everybody opened their doors to us because of Gene. We knew how important this story was and that people should hear this story. And we were very lucky, because people were so open and welcoming because of Gene. At Tibet House, for example, the director Doboom Rinpoche gave us permission to film and told us so much and was so welcoming. We got to see some of the original forewords to the texts, in the beautiful library there with all the books. We got to meet Mangaram, who told us so many stories about Gene. Mangaram really was Gene's right hand since the beginning. The two people we have to thank for helping us tell this story from the beginning is Mangaram and Gene's sister Rosanne.

From there we went to Dharamsala, then back to Delhi, and then Namdroling and then the Bon monastery. Situ Rinpoche's monastery Namdroling was fabulous. Then when we got to the Bon Menri Monastery, we realized how close Gene was to the Rinpoche. The road there was quite difficult actually, and I was very worried about everyone including the driver. There were mudslides on the journey. Gene and Mangaram were always calm because they had lived through this, but it was new for us. And then there was a cliff where we had to just get out and push the car.

We were hours late getting there because of the mudslides. The monks couldn't wait for him to get there. Watching them all, watching all the monks come down to greet Gene, to see the love they had, we knew that Gene was so revered because of the help he gave them. Gene had known them since they had escaped Tibet. It was such a close bond that he had with the abbot of the monastery, Menri Trizin.

It was almost like Gene surprised us. We had studied and prepped for this. But then to see the Bon, and to see how similar they were to the four main sects but also to see the difference was so interesting. And it was beautiful to learn the stories of their friendship, and to see the love they had for each other, as friends and what they had been through. There is a photograph in the book with the two of them, where Menri shows the text that he escaped with. That's what he escaped with, the catalogue of the texts of his original monastery of Menri in Tibet.

Gene with His Holiness Menri Trizin, the abbot of Menri Monastery, who shows him the text that he carried across the Himalayas.

Gene with His Holiness Menri Trizin, the abbot of Menri Monastery, who shows him the text that he carried across the Himalayas.And how smart was that? If you know you can't take the books, at least take the catalogue to remember what was there. And finally when we interviewed Menri, all of a sudden, he pulls out a little sack around his neck, and he says, 'I showed you the book of the catalogue and then Gene gives me this.' It was a thumb drive with the e-catalogue on it. Gene had given it to him so that he would never be without his catalogue again, so that he could always have it with him. We were all in tears, realizing how much these men had been through together.

You talk about digitizing and you watch different programs on it, but these were the original guys. They were doing it. They were taking stuff and microfiching and duplicating and printing, and Menri Trizin was carrying that little thumbdrive around his neck—everything to preserve the words of the Buddha.

Gene kept saying, look at what the next generation is doing. And this was before Iphones. Gene was so excited about the next generation of preservation. And they were so excited that the Dalai Lama had been there. But Gene never wanted to talk about the Dalai Lama. We weren't allowed to include anyone in the film that had controversy with China.

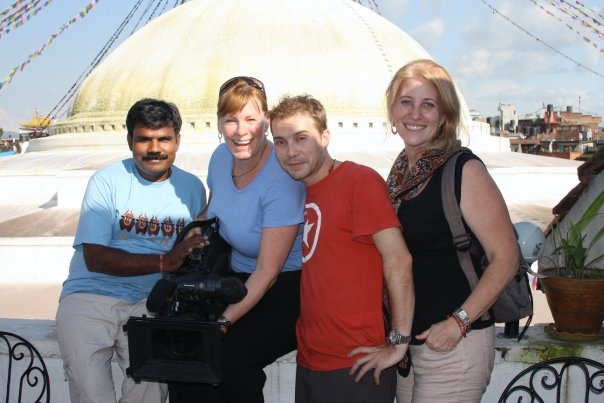

Digital Dharma film crew. Rajesh Kumar, Tamela Knapp, Wade Muller and Dafna Yachin in front of the Boudha stupa, Kathmandu, 2008.

Digital Dharma film crew. Rajesh Kumar, Tamela Knapp, Wade Muller and Dafna Yachin in front of the Boudha stupa, Kathmandu, 2008. Q: What's your favorite memory of Gene?

Gene in crocs circumambulating. I think the time at Menri Monastery is probably my favorite, seeing Gene and Menri Trizin together. I met Gene in 2005 and by 2011 he was gone. I was very lucky to spend very concentrated time with him. They say treat everyone like they are the Buddha and he did that. He treated everyone with such respect. He remembered everyone's name, what they did, what they studied. I never met anybody with the kind of memory and kindness that he had.

He could be strict. When he didn't want us around, he let us know. We thought we were going with him when he was being honored in India and Gene said no. He was so honored to begin with, and so humbled to receive this award, and he didn't want a filmmaking crew following him around for that. Noa Jones was already invited to the event by another group, so she sent us photos. We were lucky that she was there. Gene had his ego in check. He let us do this just to make sure that TBRC survived. He always said, the story's not about me, it's about other people. But we were making an American film, and it was an American story. It's a story about the past that we had to tell about the present.

I mean, a Mormon from Utah helped preserve Tibetan literature! So much of it was timing. He was in Seattle when they brought the lamas to Seattle, and that's how it all started. I really loved Gene and when he died, it broke my heart. My father was so similar to Gene. My father did everything for others. Gene was the only other person I met, like my father, that was so scholarly and so kind.

I have told so many people's stories but the biggest was being able to tell Gene's story. I feel lucky and hope the next generation gets to understand exactly what he did.

Q: What's your next project?

A: We have been shooting this for five years. It's called Alexander McClay Williams. Alexander shines a light on America's history of injustice. Before Emmett Till, before George Stinney, Jr., before Trayvon Martin – before the seemingly endless roster of victims of racially motivated murders – there was Alexander McClay Williams. The youngest person to die in the Pennsylvania electric chair. Alexander was a sixteen year-old teenager, who was accused of murdering a school matron. He was accused, convicted and executed. Professor Samual Lemon, the great grandson of the the attorney who defended Alexander, Alexander's only living sibling and her extended family, along with the murdered Matron's niece, join together to try and clear Alexander's name and conviction, posthumously. It's a powerful story about a horrific miscarriage of justice. Three months ago, Alexander was exonerated in court, nearly 90 years later. Philadelphia has the highest record of wrongful convictions in the country. A place that's supposed to be the birth place of American freedom. At least this film has a happy ending, with Alexander's exoneration. I realized it's a difficult project, and we had to think of clever ways to illustrate history. We hope we can get backing or distribution to turn this important story into a series or a documentary.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.